On Caches - SIEVE

WORK IN PROGRESS

This blog post is a work in progress and may have incomplete/irrelevant information. I don't recommend you to read this because it has incomplete information.

Caches are a fundamental part of computer science, seen and used everywhere. In this post, I am collecting my notes on [SIEVE], a remarkable new cache-eviction policy proposed for Web workloads, that not only has a good hit ratio but also scales (almost) linearly with the number of CPU cores the machine has. Before I dive deep into the implementation, I will take you through a brief refresher on caches, and the various extant eviction algorithms for them.

Refresher

A Cache is a structure that can be used to store frequently-accessed items, so that we have quicker access to them. Usage of caches is done everywhere, from caching web contents (CDN), DNS records, to all the way upto CPU itself. A cache is essentially a faster front to a slower data store, which is much, much larger in size compared to the cache size. That brings us to an important conclusion - not all the data in the store will fit in the cache, so we need to be selective in choosing what data we want to persist on the cache, and what data we can afford to let go. There are several cache-eviction policies available for the same:

- LIFO: Last-added item gets removed first (stack)

- FIFO: First-added item gets removed first (queue)

- LRU : Least-recently used item gets removed first

- LFU : Least-frequently used item gets removed first

As such, it is not difficult to come up with some implementations of these algorithms. A (particularly) short example of LRU cache can look like the following:LRU Cache example

int num = 0;

;

struct CacheNode* cache = NULL;

void

void

void

void*

void*

PHEW! That is a LOT of code! The meat of the matter - the only thing we're interested in the above is the eviction policy, in our LRU cache, we simply remove the least-recently-used item from the cache. The public-facing part of our code would be the find function, and every time we call the fetch_data_external_function, it would count as a cache-miss. Implementations for LFU would be similar and LIFO/FIFO would be simpler.

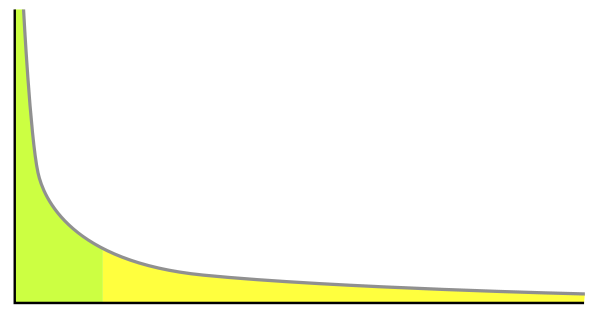

The paper on SIEVE

Now that we've jogged our memory a bit, the question remains - why do we need so many types of Cache-eviction methods? The answer is pretty evident - for different types of workloads, different cache-eviction algorithms are best suited. According to the authors, the web access patterns follow a Power-law distribution, which yields way to optimization using SIEVE method they propose on top of existing eviction algorithms.